Observation: Being HAL

I first played Observation back in the summer and immensely enjoyed it. It was an enthralling experience which stuck with me for weeks after; in fact, I still catch myself wondering about it from time to time. I was prompted to think harder about Observation when the game won No Code their second Scottish Bafta (their first being awarded for Stories Untold) and harder still when I saw Graeme McKellan speak about the game's development at an event called Games in Space, the inaugural University of Glasgow Game Lab meeting session.

While teaching constraints meant that I couldn't stay for the whole talk, it was enough to get me properly dwelling on Observation again, and I realised that I'd never written about it. This surprised me, because when a game sticks with me as much as Observation has I usually don't shut up about it. In the following post I'll rectify that error. Speaking of errors, though, it has been some time since I played through Observation, so while there are themes and moments that are seared into my mind, I might be hazy on the details. That's as good a reason as any - plus the reason that I'd want anyone reading to experience Observation for themselves - to make this a more-or-less spoiler free review.

Graeme's talk was an excellent piece for the Gaming Lab's first event, particularly given the theme.

Obligatory disclaimer: I don't know how to write about games, something that's probably quite obvious from my other blog posts. My career is spent writing about spatial skills experiments and educational practices for audiences who are primarily uninterested in anything that isn't quantifiable or practically applicable, constrained to page limits and templated formats (for any CS education researchers reading, please know that I am generalising!!) After musing for a while about how to present my thoughts on Observation, I eventually decided not to think too hard about it and capitulated everything onto the page beneath a few headings that felt right. It will probably read a bit strangely, but then again it's a strange game, so I'm not inclined to change anything.

What is Observation?

Observation is set on a space station called Observation, which has somehow ended up not quite where it's supposed to be. A crew member, Dr Emma Fisher, is separated from her colleagues and isn't sure of what has happened or where they are. The plot primarily circles around Dr Fisher trying to find her colleagues, identify what went wrong aboard the station and try to fix it.

The twist is that you, the player, do not play as Emma Fisher. You play as SAM, an artificial intelligence abroad Observation responsible for the station's overall operation. SAM does not have a body, so you spend your time flicking between stationary cameras dotted around the station, trying to piece together information about the environment. With some kind of damage having knocked SAM awry in ways that we're not initially aware of, the access that SAM has to certain areas and functions of the station change over time, expanding the gameplay organically across the station.

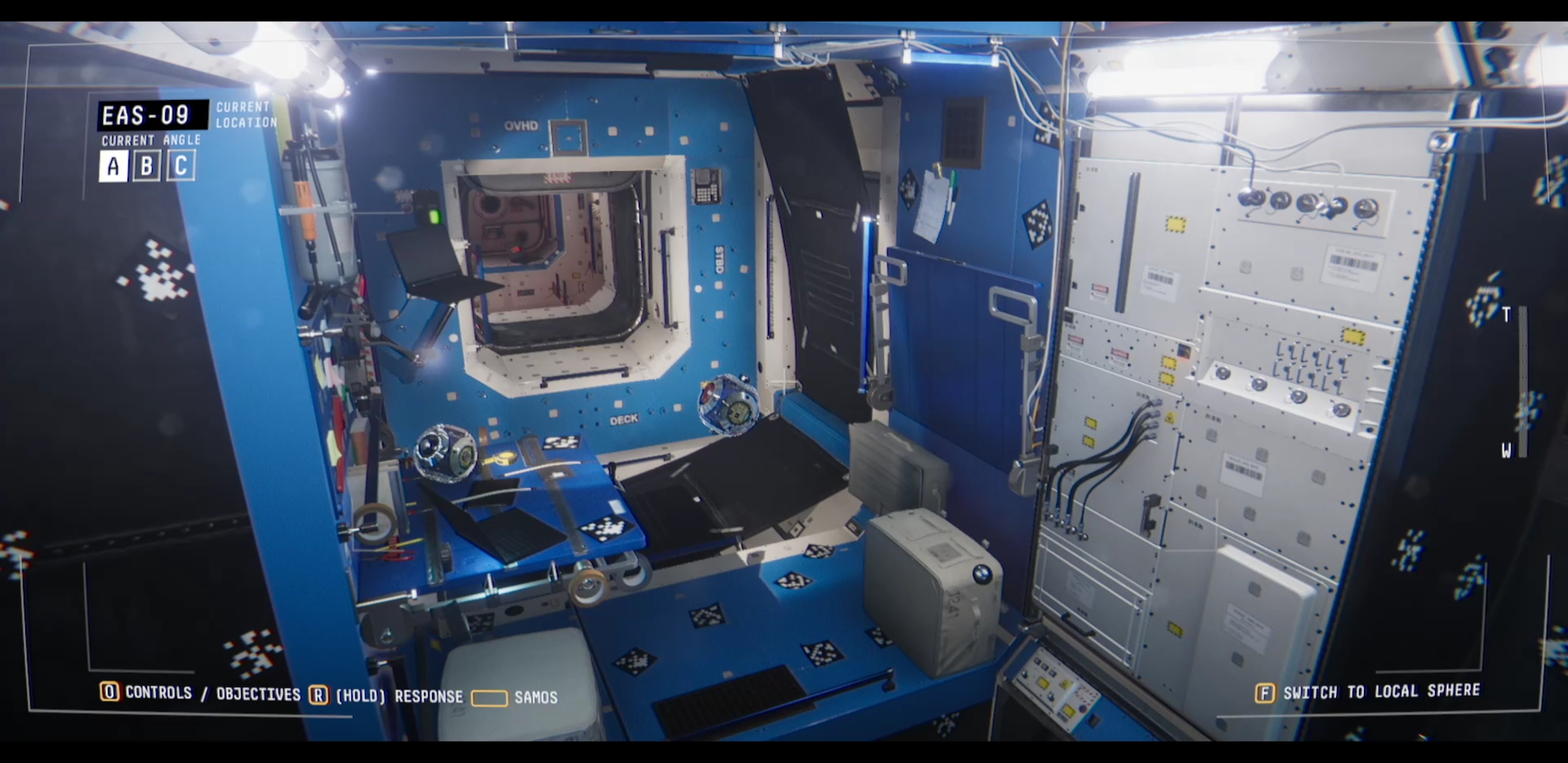

One such view from SAM's perspective.

The initial stages of the game are spent diagnosing, exploring and considering what has happened, who's fault is it, how can it be fixed and so on. But all the while, something sinister and unknowable is creeping into the plot, injecting tension and a unique brand of horror of the kind that I've never encountered in any media before.

Atmosphere and Immersion

It has been said that Observation has the same DNA as Alien: Isolation - this makes sense, given how much cross over there was between the development teams. While Graeme detailed the creative process for the design of the space station being heavily based on the ISS, the concept artist for Alien: Isolation's Sevastopol filled in the gaps. The game's director Jon McKellan - Graeme's brother - was a UI designer for Alien: Isolation. The vocal talents of Kezia Burrows and Anthony Howell (Amanda Ripley and Samuels) were used for Emma Fisher and SAM respectively. Other roles, including character artists, story supervisors and game designers from Alien: Isolation were also involved in Observation's development in some capacity, so it stands to reason that the game has a very similar feel.

Lots of Observation screenshots could be mistaken for Alien: Isolation - astonishingly, the game was entirely built in Unity!!

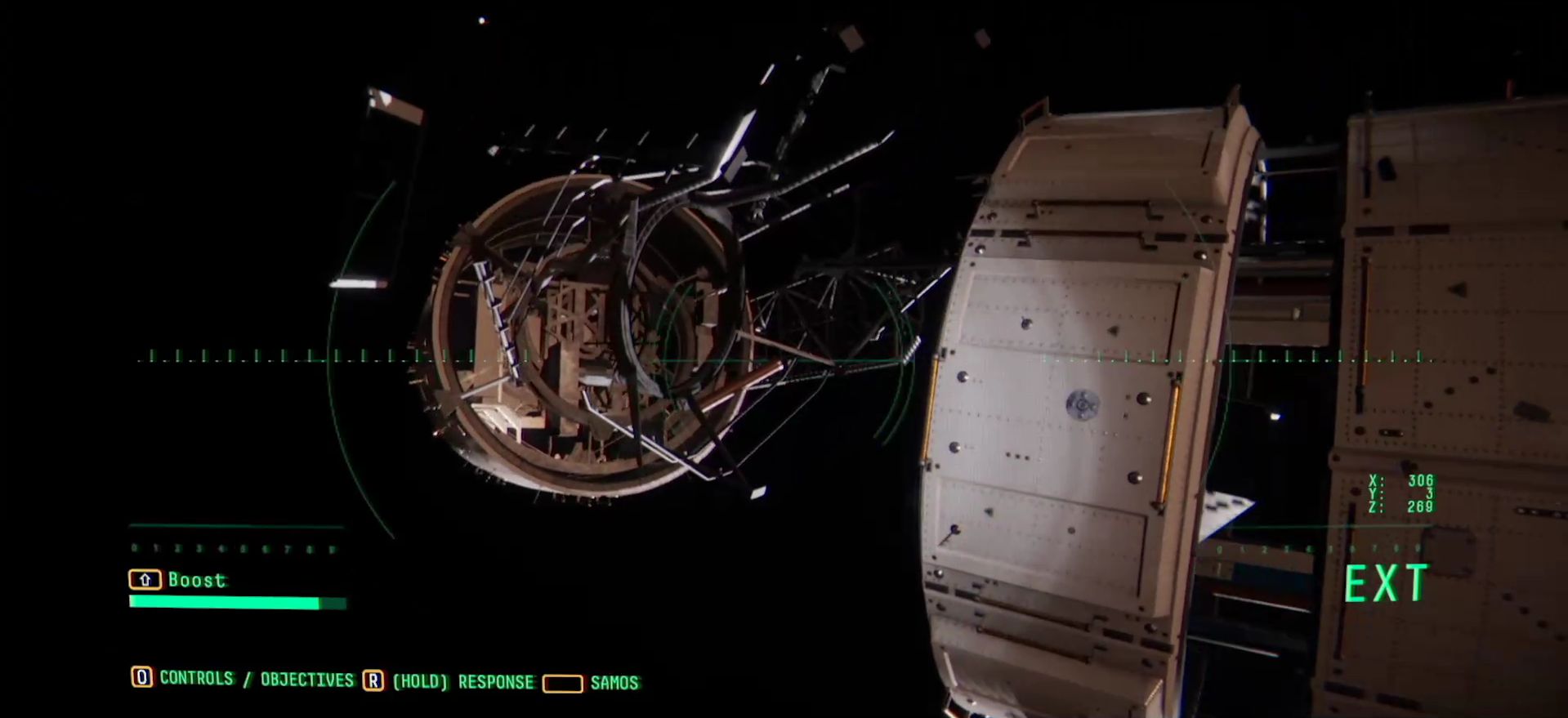

And like Alien: Isolation, the atmosphere is wonderfully grim and foreboding. Observation doesn't have a clear cut antagonist, but still manages through various means to generate a deep sense of chilling dread which permeates the game. A big part of it is the fear of the unknown, which works remarkably well for a game where you play as an AI, famously omnipotent constructs in popular culture. This is best illustrated by an example from early in the game: SAM is able to detect that one of the station's modules is somehow incorrectly secured - the bolts fitting it to the adjacent module are failing to lock. This is all the information SAM has, so Fisher sends him (it?) out in a drone to get a proper look. I will never forget the sinking feeling that I got in my stomach when I first saw the problem, played up by the excellent sound design and the fantastically built tension rising in the moment: the pod had been ripped apart, torn and twisted, causing the bolts to buckle and snap. That early discovery was educational: SAM's sensors can tell when something is not right, but just how not right is never clear until you catch it on camera.

The game is peppered with moments like this. Another early incident is a fire breaking out somewhere on the station - SAM gets an alarm and even an indication of which module, but in order to identify just how serious the problem is requires some fast camera flicking to actually see the damage. From the sensors alone, it's impossible to tell if the fire is a smouldering electrical short or a blazing inferno. It creates a precarious relationship between the station and the AI. The sensors will tell you what is happening on the most fundamental level possible, but what the data actually means is terrifyingly ambiguous. It's an excellent tool for building the tense and edgy atmosphere.

No Code have also absolutely nailed the emptiness of space. SAM occasionally has to leave the station as a drone, which were some of the spookiest moments in the game. There's nothing out there that can get you... but crucially, there is nothing out there. The blackness and scale of it feels oppressively bleak, conveying a sense of frantic helplessness about the whole situation. Something about floating around the station completely untethered makes the feeling far worse, even if there is no real risk to SAM. The silence and the vastness is captured so beautifully chillingly.

Space: dark, cold and empty

Graeme had a very interesting point on one of his slides: all the visuals, audio and UI are diegetic. Gratefully, Graeme explained this for us who are not artistically inclined! It means that every sound, graphic and UI element is built into the story, being part of the narrative. Every buzz, alarm, image distortion and progress bar exists because it is what SAM sees. User overlays and objective markers exist not as a supernatural beacons or impossible HUD elements, but as part of the built-in interaction, with a tangible, in-game reason to exist. Examples from other games spring to mind: Isaac's health bar in Dead Space, the colour of Spyro's dragonfly, the helmet HUD of Republic Commando and it's in-game clip capacity measurements.

Some examples of diegesis in other games

In my experience, diegesis in games isn't awfully common, and less common is a game which fully commits to the principle. Observation is one such game. The level of immersion is peerless; just another factor of the game which entirely sucks the user in and makes it stick in the mind.

Gameplay and Narrative

Gameplay and narrative can be difficult to blend, with many games intercutting the "game" with plot heavy cinematics, set pieces and cutscenes. Observation is not devoid of cutscenes, with several moments scattered throughout the game of more-or-less watching some human characters from a fixed perspective, but Graeme explained to us another of Observation's development philosophies: design always driving narrative forward. This isn't strictly limited to gameplay, of course, with the design of the station laid out in such a way that it opens up and expands outward as the game progresses.

But ultimately, everything you do as SAM is intrinsically driving the plot. Every time Emma asks for something for SAM to do, it's to further her understanding of her situation or helping her to fix problems she has, with the ultimate goal of getting home. The story generally moves slowly: if Dr Fisher asks you to check the sensors in one of the habitation pods, they might indicate a power loss. Okay then, SAM can sync with a sphere drone, fly over there and turn the power back on. Once there's power, SAM can then turn on life support, allowing Emma to enter the hab. Emma may then interact with a (biometrically locked) computer to locate the whereabouts of a missing crew member in a part of the station only accessible from space. And so it continues.

Ultimately the sensors were right: the pod *wasn't* properly connected!

It may sound dull, but in fact the loop is very compelling. The way the narrative flows and fluctuates with each new objective keeps you on your proverbial toes, with a definite sense of progression throughout.

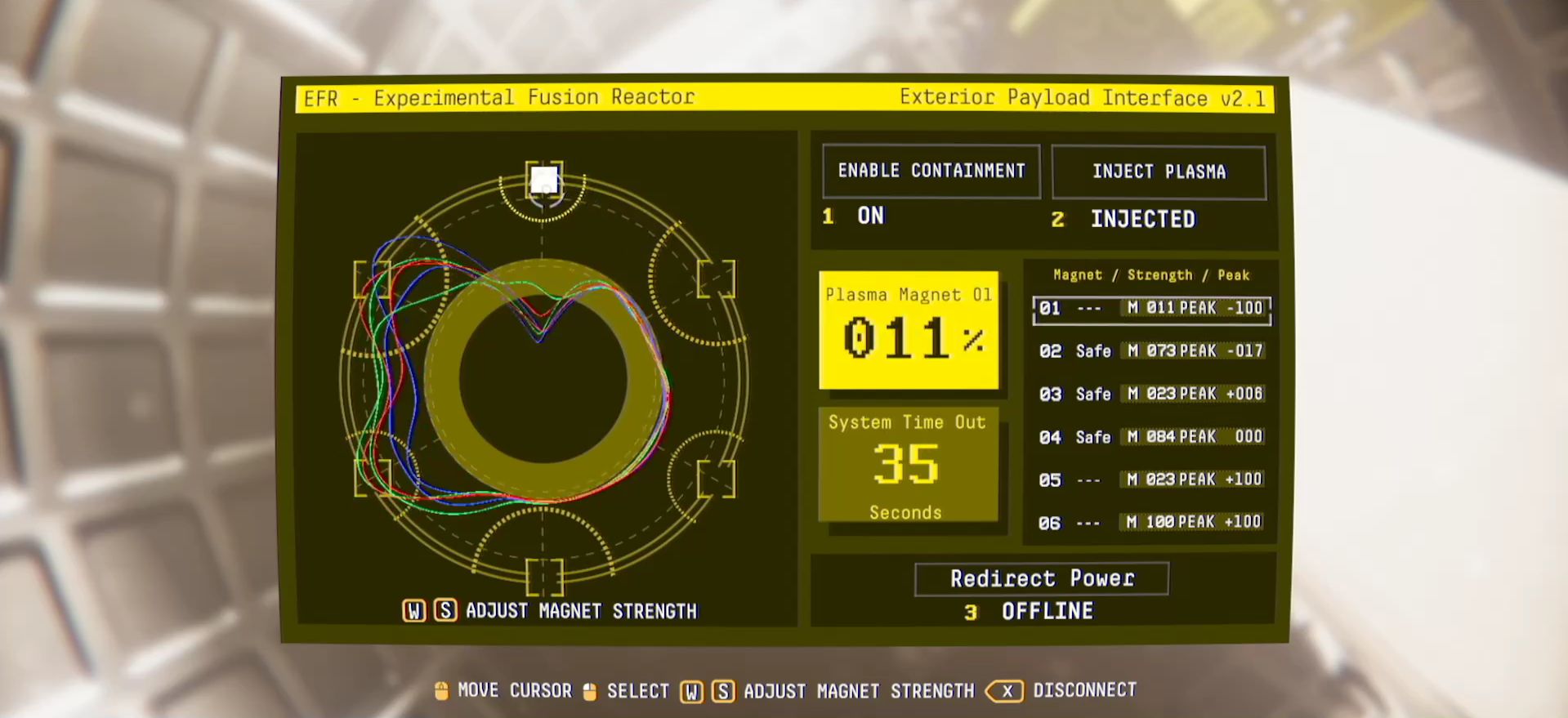

But what is gameplay actually like? It varies. Sometimes it involves switching between static cameras around the station to find an interactive interface. Often in consists of doing the same thing but from the confines of a sphere drone. Usually every action (unlocking doors, releasing clamps, realigning communications dishes, etc) involves a puzzle. The puzzles won't be unfamiliar to people have played puzzly games before: they often involve matching symbols, simple number balancing or choosing the right sequence of symbols, that sort of thing.

That again makes them sound awfully dull, but once again Observation's development philosophy comes to the fore: Graeme tells us that "science fact" informed the puzzle design. I can't claim to know anything about space or the mechanics of space traversal, but the puzzles all feel... correct, somehow. Performing a quick sequence of actions to disengage a lock or arm a blasting cap feels like the right interaction. Puzzles with computers feel digital and fuzzy; puzzles involving physical, tangible movement felt mechanical and analogue; it's hard to describe how it all fits together, but it does. I don't think I once encountered a puzzle and thought that it was contrived or silly or out of place - clearly a lot of thought has gone into building puzzles which break up the game and inject some challenge while also being perfectly aligned with the thematic and narrative design.

All the puzzles just felt *right*

Observation also has a unique interaction mechanic in the form of what could be called "responses". Characters may pose SAM a question, which he will have to refer to in-game interfaces and objects to answer. Once SAM has identified the information required, you can enter response mode, allowing you to select the data, view or some other artefact to create your response. For example, Fisher may ask for the status of one of the hab modules on the station. By opening up the station's monitoring interface, you can see the station map and identify the module. Perhaps it will read that it's safe for traversal, or may read that its depressurised, or maybe SAM's sensors won't be able to pick up anything at all. Whatever the result, switching to response mode and indicating the data you want to report back about the module will prompt SAM to pass the info on. The only comparison I can make is something like Papers, Please, but with looser rules and more nebulous regions of interaction.

Once again, the limitations of SAM - the machine limitations - are important. They are significant in driving the tension to a fever pitch as the game progresses. More than once, Emma has to use her voice to authenticate herself, and on occasion SAM's sensors will flash red and indicate that the pattern doesn't match. At this point, official protocol indicates that you should reject the authentication, but SAM still has the freedom to make the final decision. It's very clearly Emma, the same person we've been helping since the start of the game... isn't it? It must be - so why would the voice match fail? Is there something wrong with SAM? With Emma? The questions creep and hang at the back of the mind, eventually sowing the seeds of doubt in every action.

And in the darkness...

A lot of Observation is spent dealing with very human things. Sometimes these things are virtually mundane and trivial. Sometimes they get dark, foreboding and chilling. And sometimes it's worse than that.

Throughout the game the player will encounter curveball that they cannot explain, that SAM can't compute and simply doesn't attempt to. That's the limitations of the machine rear their head again: flashes of unknowable beings and bizarre images that don't make sense to SAM. But SAM doesn't get scared or feel the need to explain what he's just seen: he won't interact with the experience because it is essentially of no consequence. It gives the player a feeling akin to being trapped. We know something is not right, that something sinister is afoot, but SAM doesn't perceive it in the same way and therefore doesn't pursue it.

Never before has a memory game been so compelling

These encounters occur and are immediately forgotten about, as if they were never witnessed, but the player knows. Once again, the presentation of this theme is masterfully designed and implemented, setting up a hard edge to the whole game that occasionally appears abruptly before slowly sinking away, ever-present but invisible. It's something to watch out for!

I hope that this has inspired someone to pick up Observation and try it for themselves. It's a game that has to be experienced, preferably in a dimly lit room with no distractions and stereo headphones, just to maximise on that immersion factor. It is an incredible game which fully deserves the recognition it has been awarded, and I am really excited by what No Code are working on now and in the near future.